Fellows’ corner

Dr. Shefali Sharma, Faculty, Rheumatology, PGI Chandigarh

TITLE: Treacherous Game of Vasculitis

Dr. Sumatha C Suresh, MD (MED)

Dr. Vineeta Shobha, MD, DM (Prof. and Head)

INTRODUCTION:

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a medium vessel vasculitis that can form microaneurysms in vasculature, affecting various organs. PAN can show a wide spectrum of involvement, from single organ involvement to multiorgan manifestations. According to the American College of Rheumatology, the presence of three of the following 10 criteria are considered diagnostic of diseases: weight loss, livedo reticularis, testicular pain or tenderness, myalgia or myopathy, neuropathy, hypertension, renal impairment, hepatitis B infection, abnormal arteriogram, and positive biopsy results. Here we report a case of PAN with cutaneous and systemic involvement that was rapidly progressive in spite of treatment with IV immunoglobulin, high-dose parenteral steroids, and cyclophosphamide.

CASE SUMMARY

A 27-year-old male with no known comorbidities, a nonsmoker, presented with a history of swelling over the dorsum of the left hand associated with severe pain and tenderness and with a local rise of temperature. He was treated as cellulitis for the same without relief. He started to notice hyperpigmentation over his right hand and the flexor aspect of his right forearm a week later. He also had a history of polyarthritis, which is symmetrical, large, and small joint involvement not associated with EMS for almost two weeks before presenting to us. He also had associated myalgia. He also reported significant weight loss.

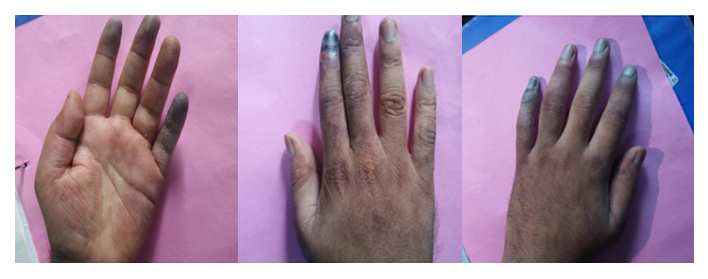

On examination: He had an erythematous nodular/plaque-like lesion over the left hand dorsum, left hand swelling extending up to distal one-third of forearm, livedoid rash over the left forearm, nodular plaques with eschar-like lesion over the right lower limb. Additionally, discoloration and swelling of the right dorsum of first and second digits were noted. Tenderness was noted over all muscle groups with painful weakness predominantly of proximal muscle groups. The patient had daily fever spikes while in hospital.

In v/o of the above findings, a working diagnosis of infectious panniculitis, leukemia cutis, Behcet’s disease, and Sweet's syndrome was considered.

His lab workup revealed leukocytosis (persistently >30,000, neutrophil-predominant), thrombocytosis (>6 lakhs), elevated CPK (1654 U/L), LDH (279 U/L). To rule out leukemia, bone marrow aspirate was performed, which revealed hypercellular marrow with increased eosinophils, plasma cells, and megakaryocytes but no abnormal cells. Immunological workup including ANA, ANCA, PR3, MPO, myositis autoantibody profile, cryoglobulins, rheumatoid factor, and APLA was negative. Additionally, viral markers were negative. Muscle biopsy was performed in view of elevated CPK and severe myalgia; it showed subtle neurogenic changes. His skin biopsy showed fibrinoid necrosis consistent with medium vessel vasculitis favoring PAN; immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, IgA, IgM, C3—suggesting pauci-immune vasculitis. In v/o of nodular skin lesions, neurological symptoms, skin biopsy showing fibrinoid necrosis, a diagnosis of PAN was considered. High-dose parenteral steroids were initiated with a moderate initial response. However, he continued to have fever spikes and developed new-onset neurologic deficits, namely, weakness of distal muscles of lower limbs (foot drop), left upper limb (wrist drop), and associated paresthesia while on high-dose parenteral steroid. ENMG at this juncture showed left radial nerve motor axonal neuropathy. In v/o progressive disease and poor response to high-dose parenteral steroids and rapidly progressing neurological symptoms, IVIG 2 g/kg was administered, followed by monthly cyclophosphamide pulse. At two-week follow-up, the patient’s symptoms had further worsened, in the form of worsening pain and swelling of bilateral hands, progressive rash, pregangrenous changes of right second and third digits, and persisting proximal muscle weakness. After three doses of cyclophosphamide, the patient continued to worsen, developed right index finger gangrene and pregangrenous changes in the left little finger, index and middle fingers.

Since the patient had poor responsiveness to IVIG, cyclophosphamide pulse with high-dose steroids other differentials like deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2 was considered. CT angiogram was performed; it did not show any evidence of aneurysm. His ADA2 levels were also normal. Therefore, cyclophosphamide pulse was further continued. Currently, after five doses of cyclophosphamide, the patient has improved neurologically and there is no further progression of gangrenous changes. His leukocyte count and platelets have reached normal limits. He is currently mobilizing on his own.

DISCUSSION

PAN is a disease with multisystem involvement, and is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis and leukocyte infiltration of medium vessels. Recently, a decreased incidence of hepatitis B infection has led to a reduction in the incidence in PAN. The prevalence of PAN ranges from 2 to 33 per million.1–3 The incidence of the disease rises with age, with the peak incidence noted in the sixth decade of life. PAN shows a slight male predominance, with the M:F ratio being 1.5:1.4–6. About 44% to 50% are found to have skin involvement.7,8 It has been suggested that cutaneous PAN and PAN are indeed separate, but cutaneous PAN is not just confined to the skin.9 Our patient presented with nodular, erythematous tender skin lesions, high spiking fever, polyarthritis, livedoid rash, leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis. Hence, the initial differentials considered were paraneoplastic skin manifestations such as leukemia cutis and acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis versus infective panniculitis. Classical Sweet's syndrome is characterized by pyrexia, elevated neutrophil count, tender erythematous skin lesions (papules, nodules, and plaques), which are steroid-responsive, very similar to the presentation in our patient. However, the biopsy is characterized by a diffuse infiltrate consisting predominantly of mature neutrophils typically located in the upper dermis. Leukemia cutis can be a manifestation myeloid or lymphoid leukemia with a wide variety of skin manifestations. The lesions are usually described as violaceous, red-brown, or hemorrhagic papules, nodules, and plaques of varying sizes.10 Hence bone marrow biopsy was done in our patient; it did not reveal any abnormal cells. Histopathology examination showing fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall, and negative serologies helped us to narrow down the diagnosis to PAN.

Untreated PAN with a five-factor score of 1 and above is associated with high mortality. Aggressive immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide and pulse methylprednisolone is recommended in PAN with a five-factor score of at least 1.11–13 Our patient also had a five-factor score of 1. Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment improve outcomes. In non-HBV PAN, the seven-year survival rate is 79%, compared with a five-year survival rate of 72.5% in HBV-related PAN.14 Our patient showed rapidly progressive symptoms with delayed response to cyclophosphamide pulse and IVIG that led to the suspicion of other monogenic vasculitides such as DADA2. Our patient underwent CT angiogram abdomen and ADA estimation; both were normal.

Deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2 (DADA2) has recently been identified as an autoinflammatory disease.15 DADA2 is an autosomal recessive disease that occurs due to a mutation in the CERC1 gene, which encodes for ADA. The disease is mainly characterized by chronic or recurrent systemic inflammation with fever and elevation of acute phase reactants, usually associated with a variety of skin manifestations, ranging from livedo reticularis to maculopapular rash, nodules, purpura, erythema nodosum, Raynaud’s phenomenon, ulcerative lesions, and digital necrosis.16 The most common systemic involvement of DADA2 is neurological, affecting the central or peripheral nervous system. The histopathology of DADA2 has also shown non-granulomatous necrotizing vasculitis of medium-to-small sized vessels that is indistinguishable from PAN. It has been proposed to group this disease in the ‘vasculitis with a probable cause,’ according to CHCC.16 The outcomes of DADA2 have not been well investigated, since it is a disease that has been recently identified. High-dose steroids and TNF blockers have shown a good response. Navon et al. reported that of ten patients treated with anti-TNF drugs (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab), with complete response was attained in 8, even after the failure of immunosuppressive therapies. Good results with anti-TNFagents have also been reported in other small series.17–19 Since our patient showed poor response to methyl prednisolone, IVIG, and cyclophosphamide pulses initially, DADA2 was considered. However, ADA levels were normal. Fortunately, our patient eventually responded to cyclophosphamide, and currently, the disease process has stabilized.

Acknowledgment: Dr. Lee Pui, Division of Allergy, Immunology and Rheumatology, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United Statesfor estimation of ADA 2 levels

REFERENCES

- Mahr, A., Guillevin, L., Poissonnet, M. & Aymé, S. Prevalences of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome in a French urban multiethnic population in 2000: A capture-recapture estimate. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 51, 92–99 (2004).

- Reinhold-Keller, E. Giant cell arteritis is more prevalent in urban than in rural populations: results of an epidemiological study of primary systemic vasculitides in Germany. Rheumatology 39, 1396–1402 (2002).

- Haugeberg, G., Bie, R., Bendvold, A., Storm Larsen, A. & Johnsen, V. Primary vasculitis in a Norwegian community hospital: A retrospective study. Clin. Rheumatol. 17, 364–368 (1998).

- Watts, R. A., Elane, S. & Scott, D. G. I. Epidemiology of vasculitis in Europe. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 60, 1156–1157 (2001).

- Watts, R. A., Lane, S. E., Bentham, G. & Scott, D. G. I. Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis: A ten-year study in the United Kingdom. Arthritis Rheum. 43, 414–419 (2000).

- Watts, R. A. et al. Geoepidemiology of systemic vasculitis: Comparison of the incidence in two regions of Europe. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 60, 170–172 (2001).

- Pagnoux, C. et al. Clinical features and outcomes in 348 patients with polyarteritis nodosa: A systematic retrospective study of patients diagnosed between 1963 and 2005 and entered into the French Vasculitis Study Group database. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 616–626 (2010).

- Gibson, L. E. Cutaneous vasculitis update. Dermatol. Clin. 19, 603–615 (2001).

- Nakamura, T. et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: Revisiting its definition and diagnostic criteria. Archives of Dermatological Research 301, 117–121 (2009).

- Watson, K. M. T., Mufti, G., Salisbury, J. R., Du Vivier, A. W. P. & Creamer, D. Spectrum of clinical presentation, treatment and prognosis in a series of eight patients with leukaemia cutis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 31, 218–221 (2006).

- Bourgarit, A. et al. Deaths occurring during the first year after treatment onset for polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome: A retrospective analysis of causes and factors predictive of mortality based on 595 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 84, 323–330 (2005).

- Cohen, R. D., Conn, D. L. & Ilstrup, D. M. Clinical features, prognosis, and response to treatment in polyarteritis. Mayo Clin Proc 55, 146–155 (1980).

- M., G. et al. Long-term followup of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome: Analysis of four prospective trials including 278 patients. Arthritis and Rheumatism 44, 666–675 (2001).

- R., P. & R., L. Mortality in systemic vasculitis: A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 26, S94–S104 (2008).

- Anikster, Y. et al. Mutant Adenosine Deaminase 2 in a Polyarteritis Nodosa Vasculopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 921–931 (2014).

- Caorsi, R., Penco, F., Schena, F. & Gattorno, M. Monogenic polyarteritis: The lesson of ADA2 deficiency. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 14, (2016).

- Mutant ADA2 in Vasculopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 478–481 (2014).

- Batu, E. D. et al. A case series of adenosine deaminase 2-deficient patients emphasizing treatment and genotype-phenotype correlations. Journal of Rheumatology 42, 1532–1534 (2015).

- Van Montfrans, J. M. et al. Phenotypic variability in patients with ADA2 deficiency due to identical homozygous R169Q mutations. Rheumatol. (United Kingdom) 55, 902–910 (2016).

Vineeta Shobha

Sumantha Suresh

Answer to Last Issue’s Puzzle

A 20-year-old boy presented with a history of recurrent ulcers in both lower limbs. He had had a total of seven episodes in the past year. The ulcers were painless, but had a typical punched-out character and were slow to heal. The boy’s mother said he had had two episodes of jaundice since birth: one five years before and the second 12 months before. However, he did not have any constitutional features. On examination, he has an ulcer on left lower limb lateral malleolus and on right shin, there is a shiny scar telling the course of the previous ulcer. We did not find anything significant in his cardiovascular and central nervous system examination. We noted that he had a barrel-shaped chest; the respiratory system was normal. His liver was palpable 1 cm below the costal margin, which was smooth and non-tender.

Investigations showed a normal blood count with an ESR of 75 mm at 1 hour. Live function: AST of 234 IU/L, ALT of 324 IU/L, and ALP of 321 IU/L. Total protein was 8.1 g/dL, albumin of 3.2 g/dL, and globulin was 4.9 g/dL. Kidney function and urine examination were normal.

ANCA IIF showed 3 + cANCA pattern with an anti-PR3 titer of 58 U/mL (normal <3.50 U/mL).

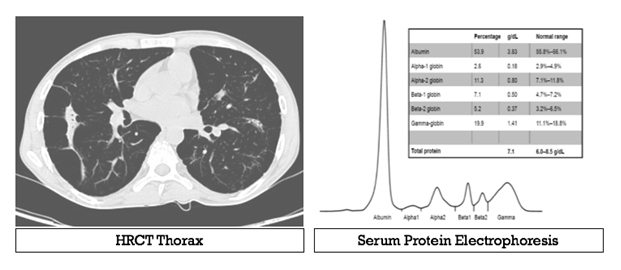

Serum protein electrophoresis was ordered. What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency with ANCA vasculitis

Clues:

Clinical: Recurrent jaundice (liver involvement) plus emphysematous chest = Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AAT deficiency) Investigation: The absent peak of alpha-1 on serum protein electrophoresis and CT thorax suggestive of pan acinar emphysema a pattern observed with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

The Interesting Association—Vasculitis Ulcer With Positive Anti-PR-3 ELISA in This Case

The Z-allele of the SERPINA1 gene is significantly associated with both PR3 and MPO-AAV.1 A proposed mechanism through which AAT deficiency exacerbates vasculitis is the priming of neutrophils for activation by ANCA. Neutrophils primed with AAT polymers express increased superoxide production upon stimulation by ANCA, leading to vasculitis.2 Alpha-1 antitrypsin augmentation therapy, though not evaluated, can be a possible treatment option in ANCA vasculitis associated with AAT deficiency.

Reference

1. C. Rahmattulla, A. L. Mooyaart, D. van Hooven et al., “Genetic variants in ANCA-associated vasculitis: a meta-analysis,” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, vol. 75, no. 9, pp. 1687–1692, 2016.

2. H. Morris, M. D. Morgan, A. M. Wood et al., “ANCA-associated vasculitis is linked to carriage of the Z allele of α1 antitrypsin and its polymers,” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, vol. 70, no. 10, pp. 1851–1856, 2011.

Dr. Chengappa, MD DM (JIPMER)

Image Puzzle: IRA Newsletter April 2019

55/female presented with a three-month history of ichthyosiform rash over the face and limbs (resistant to topical treatments) along with alopecia and new-onset psychotic symptoms. Baseline blood investigations showed leukopenia with lymphopenia with normal renal and liver function tests. Further workup revealed anti-nuclear antibody positivity with hypocomplementemia and raised anti-dsDNA titers. Her MRI brain and CSF examination were normal.What is the most likely diagnosis?

Send your answers to pujasrivastava@gmail.com

Dr. Puja Srivastava Consultant Rheumatologist

VS Hospital & NHL Med College & STAR Clinics, Ahmedabad